The power of collaborative action: highlights from our annual survey

For the Midwest Row Crop Collaborative members, industry leadership doesn’t come without its share of work—understanding one another’s priorities, resources, and ways of working requires a meaningful investment, and is one that the members believe is necessary. As a group that represents a range of activities and interests, members of the Midwest Row Crop Collaborative felt a need for a more complete understanding of the work currently underway across its membership.

To establish this, an annual survey was initiated to catalog the practices and strategies used by our individual members in projects across their portfolio that fall within the Collaborative’s scope. As a result, we have a clearer sense for where our members are investing, their curiosities, and the projects where they’ve had notable successes paired with big lessons.

One benefit of the Collaborative structure is its function as a space for open learning and reflection among an intimate group. However, our members feel that it’s critical to share lessons learned with peers, those operating within the field of sustainable agriculture, and the general public. In the coming months, the Collaborative will be sharing more lessons from its on-the-ground project work. Here, we highlight three noteworthy findings from our recent inventory.

- Where and What

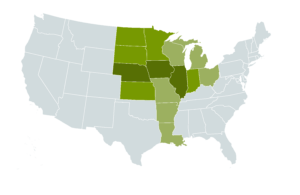

Although the Collaborative is focused on the Upper Mississippi River Basin, this map shows that members are leading, implementing, or supporting projects focused on sustainable and regenerative agriculture along the length of the Mississippi River. The Collaborative is aligned with the aspirational goals of the Mississippi River/Gulf of Mexico Hypoxia Task Force, which include reducing the nutrient loading of nitrogen by 41 percent and phosphorus by 29 percent from Mississippi River Hypoxia Task Force States by 2035. While some of the projects undertaken by individual members may be outside of the Collaborative’s geographic focus, they provide additional opportunities to advance the group’s goals, contribute to members’ knowledge, and support a more resilient agricultural system.The commodities most commonly sourced from these projects include corn and soybeans, and to a lesser degree, small grains, wheat, and rice. The sustainable agriculture practices most frequently encouraged within these member projects are cover crops and no/strip/reduced till, followed by nutrient management plans, irrigation management/efficiency, integrated pest management/reduced pesticide use, and removing marginal land from production. Some practices, like integrated agroforestry, pollinator habitat, and buffer strips are still more limited in their implementation. While members certainly don’t represent the breadth of all companies and NGOs promoting sustainable agriculture practices, these findings give some sense for where resources and effort are currently being devoted. - From Theory to Action

For each of what we consider ‘strategies’ to drive practice adoption, members were asked to share the specifics—the successes and the opportunities for improvement they’ve experienced, recommended partners, and the biggest lessons they’ve taken away from their work on these strategies. The strategy considered most effective by members, and among the most widely-practiced, was cost share, followed by technical assistance.This may come as no surprise to many, but the members with cost share programs continually reiterated that they found the greatest success by integrating cost share with technical assistance. One approach that members found useful in implementation of technical assistance programs was the enlistment of trusted advisors for farmers, ranging from agronomists to peer networks, to support the adoption of practices with knowledge and experience. Because some members found that short-term cost share didn’t help farmers sustain practice adoption over the long-term, there may be opportunity to explore additional approaches that could make transition to practice adoption more permanent.Related to technical assistance, education and outreach was a widely embraced strategy, and each member of the Collaborative that invested resources in this strategy focused on farmers as one of their primary audiences. In addition to a focus on farmers, members expanded their efforts to include a mixture of agricultural retailers or agronomists, consumers, local agriculture nonprofits, conservation staff, and commodity groups. Most of the members using this strategy felt the greatest impact was made when tapping into local networks, and a few described the importance of timing in helping farmers to move from learning to action. In one example, once the window for planting cover crops has passed, encouragement to embrace the practice becomes less potent.Members reflected that these top three most widely–used strategies were the most successful when deployed together, further reinforcing the need for a blend of social and economic elements in future efforts to scale practice adoption. - Identifying Important Leverage Points

Another recurring theme for members was the difficulty inherent in encouraging sustainable farming practices on farmland rented out by non-operator landowners. Thirty-seven percent of the Midwest’s agricultural land, dominated by commodity crop production, falls into this category. Unfortunately, the programs that successfully drive sustainable agriculture practice adoption on farmland owned by the operator may not find the same uptake on rented farmland due to incentive misalignment: renting farmers may understandably be reluctant to invest in practices that improve an asset that they don’t own or may not have access to in the future, and owners may not understand the benefits of investing to improve practices on their rented land. Resolving this disconnect is seen by members as critical to widespread practice adoption, and our members are piloting various methods of non-operator landowner outreach with local implementation partners.Collaborative members also identified a need for varied financial support for farmers through the transition to sustainable practices: some mentioned possibilities related to crop insurance premium reductions, while others expressed a desire for banks and lenders to consider sustainable practices in deciding their loan terms and valuation of land. Incidentally, two of the Collaborative’s Systems Change Pathways are exploring these possibilities—one dedicated to De-risking Practice Adoption and the other to Conservation Finance. Both are concerned at a base level with the social and economic risks associated with adopting sustainable practices.

Of all the insights that members of the Collaborative uncovered in this cataloging process, one element was repeatedly described as essential in each strategy’s success: strong partnerships. While project partnerships were seen as time-intensive and sometimes even unwieldy, each member expressed sincere appreciation for the power of partnerships—those in which the partners had clear roles, aligned goals, and complementary capacity were especially prized.

At a time where individuals, communities, and systems are up against incredible challenges, the value of finding—and being—good partners becomes more apparent than ever. While we make our way through this demanding and rewarding process, we will continue to offer our own knowledge and experience to advance the work of others in driving the transition to a more sustainable food and agriculture system. As a collaborative, we look forward to sharing more of the learning from our project work in the coming months.

If you see alignment or overlap between your work and ours, please reach out to us—we’d love to hear about it.